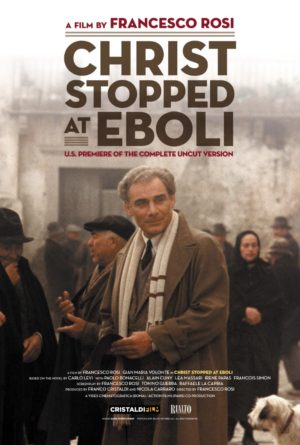

The story and landscape of Lucania are in the spotlight during the month of April. A rare, uncut version of Francesco Rosi’s 1979 film “Christ Stopped at Eboli” is being shown at the Film Forum in New York City’s West Village. The screenplay was adapted from the book by Carlo Levi, a doctor, writer and painter from Torino who was exiled to the southern region of Lucania (today, Basilicata) because of his political beliefs. The year was 1935 and Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Party was in power. Levi was forced into exile due to the silencing of those who spoke out against fascism.

The story and landscape of Lucania are in the spotlight during the month of April. A rare, uncut version of Francesco Rosi’s 1979 film “Christ Stopped at Eboli” is being shown at the Film Forum in New York City’s West Village. The screenplay was adapted from the book by Carlo Levi, a doctor, writer and painter from Torino who was exiled to the southern region of Lucania (today, Basilicata) because of his political beliefs. The year was 1935 and Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Party was in power. Levi was forced into exile due to the silencing of those who spoke out against fascism.

The uncut version is divided into four parts and lasts approximately four hours. The most striking difference from the two hour version is the visual decadence. The cinematographer, Pasquale De Santis, brother of director Giuseppe De Santis (Bitter Rice) was a longtime collaborator of Francesco Rosi. It’s obvious from the composition of the shots and the long pans of the unique Lucanian landscape that much research and location scouting was done prior to filming. Francesco Rosi had a clear talent for expressing the human spirit and the plight of the underdog as he also did in films like “Salvatore Giuliano,” “Tre Fratelli” and “Lucky Luciano.” He could show the beauty of a people and culture without glamorizing them and their hardship without demoralizing them. He so eloquently achieved this in “Christ Stopped at Eboli.” The richness of the lighting gives allure to the impoverished surroundings and the striking natural landscape accented with olive trees and wild flowers gives a sense of affluence and abundance.

[“Christ Stopped at Eboli” begins with Levi (Gian Maria Volontè) years after returning home. Lost in his nostalgia for the peasant culture he grew to love, he gazes at the portraits he created. This moment of reminiscing turns into a flashback of his first day arriving in southern Italy. The tale begins at the rail station in Eboli, a town located in Basilicata’s neighboring region of Campania. As Levi descends from the locomotive, he sees an abandoned dog with a sign around his neck asking whoever finds him to take care of him. Unbeknownst to Levi, the dog follows him and Levi decides to keep him, naming him Barone.As Levi transfers to a small bus in the town of Pisticci, we see a shot of a calanchi mountain range, which is a signature part of the sprawling landscape of this part of Basilicata. The shot eventually widens to show the details of the magnificent calanchi situated upon the rugged terrain. Consisting of clay, and formed by erosion due to wind and rain, the literal translation of calanchi is “badlands.” In Basilicata, they’ve often been described as resembling the surface of the moon.

As the vehicle approaches the hilltop town, Levi is visibly shocked and saddened to see the extreme poverty and desolation of the region. After spending an afternoon walking through his new town, Gagliano, the differences from the North are immediately apparent. They are not just physical differences, but also differences in behavior and culture. It’s worth mentioning that the actual town in which the film was shot is Aliano. Gagliano is a fictional name.

The second part opens with a bird flying eloquently along the calanchi. Making use of the spectacular natural set that is Basilicata, Rosi does not hold back. The region is nicknamed “Land of Cinema” because so many directors have shot there through the decades and clearly Rosi’s creativity ran rampant among the infinite wilderness and ancient stone structures. Levi spends his time trying to ease the culture shock by exploring his new surroundings and talking with the inhabitants of the town, asking them many questions. Although he has not practiced medicine, he earned his degree and as far as they’re concerned, that qualifies him to treat them whenever they fall ill, which turns out to be quite often.

In the third part of the film, Levi’s affection for his new friends grows stronger as does his appreciation for the plight of the peasant. He reads about the centuries of battles that hardened their hearts and broke their spirits. However, as tragic as the story is, there is an underlying humor. This is a strong characteristic of the people of Lucania. No matter how bad things get, they always maintain their sense of humor and sense of hope. Anyone who has spent time in the region will notice this quality right away. As one of those people, the most powerful line for me came when Levi was sending his sister off after a visit. “Truth is I’ve always felt like I lived here.” There is something so warm and welcoming about the people of Lucania, they make you feel like you’ve known them all your life.

As the film winds down in the last part, Levi’s affection for the peasants turns into a strong bond that forever changes him. Perhaps the most moving scene in the film comes as he departs in the rain and his dear friends and their children follow the car on foot reaching in through the open window to shake his hand and wish him well. This is where Gian Maria Volontè the actor metamorphoses into Carlo Levi. It’s as if Volontè himself became attached to the lucani while he was shooting the film and empathizes with Levi’s heartbreak in leaving them.

We are looking into a key scene that took place in the final part in which Carlo Levi talks with Gagliano’s mayor about the briganti freedom fighters and the peasants’ never-ending struggles with red tape and government. He referenced the Siege of Melfi where he believes it all began, because up to that point, the region of Basilicata or the South for that matter had its own wealth. He went on to explain that the battle had a far-reaching effect on Lucania because not only were the riches taken and the city of Melfi destroyed, but the people were also killed. How does a culture recover when much of the population is wiped out? Today, when we speak of poverty in the South of Italy, it is worth noting that even though it was a few hundred years ago, the Siege of Melfi forever changed the region of Basilicata and was a monumental cause for the mass immigration of the early to mid 1900s when our own descendants fled for American shores.

It is difficult to find information in English about the siege, which took place in the 1500s. There is information about the conquest of the Normans in 1053, but very little about the devastation that took place in the middle ages. So, I turned to Raffaella Sacco, a Matera native and avid history buff with endless knowledge about the history of her land. She received her doctorate in Architecture and Engineering at the University of Pisa. She left her region of Basilicata to study in the North because she felt that she could get a better education with less politics and red tape. When she arrived there, she found that many of her professors were of southern origins, validating her feelings. She told me that after earning her degree, she returned to the south because she believes in its redemption. “If all the best minds continue to go away, how is it possible to redeem it? I am from Matera and my city is the emblem of this desire for change. It is the third oldest city in the world with man continually living there since prehistoric times. It is a wonderful city- ancient and sacred. It is the city from which the redemption of southern Italy will start again. I am sure of it!”

It’s important to mention that Monte Vulture, a now dormant volcano with two small recreational lakes, is a point of reference on this topic because the towns surrounding it are in very close proximity to each other. These days, there is a friendly community of young winemakers who are building the local economy and tourism sector. Wines made from the area’s renowned Aglianico grape, are distributed throughout the world, putting Basilicata on the map as one of Italy’s quality wine producers.

What was southern Italy, Basilicata in particular, like before the siege?

Southern Italy was known as the Kingdom of Naples. Its wealth was due to various European rulers. At the end of the 14th century, Basilicata was involved in the bloody battles for the succession to the throne between Louis I of Hungary and Charles of Durazzo (who became Charles III King of Naples), with the looting of the Vulture area by the Hungarians.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, there was a general economic recovery: signs of an increase in commercial activities occurred in well-connected centers such as Venosa and Matera and substantial population growth was recorded. The latter had to contribute to the immigration of the refugees from Constantinople following the fall of the city under Ottoman rule. Between 1450 and 1480, numerous groups of Greek and, above all, Albanian exiles arrived at the Ionian coasts following Giorgio Castriota Scanderbeg the leader who had fought on the side of Ferdinand II of Aragona. These new communities mainly repopulated the Vulture area (Barile, Rionero, Maschito) and then settled in San Chirico Nuovo, Ruoti and Brindisi Montagna. In Matera, instead, the Schiavone (slaves) founded a neighborhood, digging the dwellings in the part of the Sassi still known as ‘Casalnuovo’.

What can you tell me about the actual siege?

France and Spain had been competing for some decades against both the Duchy of Milan (northern Italy) and the Kingdom of Naples (southern Italy; in the center of Italy there was the reign of the Pope). This conflict turned a large part of Italy into a battlefield. After the discovery of America in 1492, the Spaniards and the French continued their expansion activity in both the Americas and in Europe, focusing on the Italian peninsula for its great wealth. They inflicted a crushing defeat on the French in Pavia (northern Italy) in 1525. Leaving aside the French, at least temporarily, Charles V thought it was time to punish the Pope, Clement VII, for his pro-French policy, which led to the formation of the Cognac League, which ultimately resulted in the sack of Rome (May 1527). The horror of the Lanzi’s atrocities (but the Spanish soldiers, however catholic, were no exception) and for the sacrilege inflicted on Rome shakes the whole of Europe. Carlo – king of the very Catholic Spain, as well as emperor – whose events may have gotten out of hand, is forced, politically, on the defensive. The French think it is a good opportunity to justify a new descent in Italy, in search of a rematch, and to denounce definitively the harsh conditions (Treaty of Madrid) that they had to accept after the Pavia debacle. With strong English economic support, they send a strong army into Italy under the command of the Lautrec. Just one year later, they advance towards the South. The Siege of Melfi began in the wake of the dismay caused throughout Europe by the brutal conquest of the Eternal City and the imprisonment of the Pope by the troops of Charles V. The Siege of Melfi was probably the most bloody massacre in the history of the city as it was considered a strong economic and military market. The Melfitan resistance fought back but it was short lived. The French artillery massacred the Melfi defenders and caused fires along the walls. Although rapid, the battle was bloody and caused huge losses.

What was the area like after the siege?

The decision to attack Melfi decisively influenced the final outcome of the war. In fact, after setting Melfi on fire, the French were able to reach Naples in an orderly manner and organize an effective defense, so much so that the siege of the city was transformed (in truth for many reasons) into a disaster for the French army. The event had serious consequences on the life and economy of the city of Melfi so that in the years immediately following, special measures were taken to help with its repopulation. In particular, the citizens of Melfi, a city declared “most loyal” in Naples, were exempt from paying taxes.

In the film, there is a lot of talk about the brigands. Were the brigands born of this war or did they exist before?

The official historiography tends to give a negativity to the term brigand. More accurate studies tend to identify this name by valiant citizens who stood up against foreign domination, a bit like it happened with the Siege of Melfi. The term “Brigand” was coined by the French to define those southern rebels who opposed the French invasion. The Lucanian brigands, on the other hand, were those who carried out the city’s resistance to the Savoy invasion (Piedmontese) in the nineteenth century. The official historiography tells the story of 1000 brave volunteers headed by Garibaldi who reached southern Italy to implement the unification of the boot. The true story is very different. The Piedmontese, after having occupied Sardinia, aim to also take the south of Italy, above all its riches. They were assisted in this occupation by the British who could thus see the elimination of a strong antagonist state. The Bourbon Kingdom of Southern Italy was the third world power, resting on a large gold reserve and an advanced industry. Garibaldi was chosen precisely because, after having participated in an attempt to invade the Kingdom of Sardinia, he set himself first to be a pirate in the wake of the Bey of Tunis and then was forced to flee to South America to avoid being hanged. So he was involved first in the theft of horses in Peru and then he practiced piracy for the Asian slave trade- certainly not the saint he was claimed to be by Renaissance history. And if it was true, how would a small group of thousands of volunteers outperform such a strong state? On the same day, 20 October 1860, the dictator, who exiled bishops, archbishops and cardinals, pardoned all those sentenced to life imprisonment and jail for common crimes. Garibaldi made those criminals officers, magistrates, aristocrats, priests and friars. As for the land, it certainly was not in the hands of the peasants, towards whom he showed contempt (he considered them “servants of the priests” because they did not associate themselves with his mad red shirts), but of the Piedmontese State, of the aristocracy and of the southern land bourgeoisie, who immediately understood, as Tommasi di Lampedusa tells us in his “Il Gattopardo,” that it could very well change everything, even putting on a red shirt, without changing anything, or perhaps, gaining even more. It is no coincidence that after the conquest of Sicily, Garibaldi found more friends in Turin and in London than in the South.

In the film, Levi said that the South was never able to recover from this war. Based on your knowledge of history, do you feel this is a fair assessment?

Carlo Levi was born in Turin in 1902 and completed his training between northern Italy and Paris. He knew almost nothing of southern Italy except when he was sent into exile for his anti-fascist activity, to Grassano first and then to Aliano. For this reason, his discovery of Basilicata becomes a bit the global representation of the southern Italy. The Siege of Melfi therefore becomes the emblem of the subjection of Basilicata, plundered by foreign peoples. Until then, however, the Vulture-Melfese had experienced great splendor as is visible from the fact that Frederick II, one of the most important figures of the Middle Ages, had his castle built in Melfi from which he promulgated in 1231 the famous laws “Costitutiones Augustales”, the first written text of organic laws of the medieval period. He also built the Lagopesole castle as a hunting estate. He was also able to have the Castle of Lavello and San Gervasio built, confirming that these places experienced a period of great splendor until the sixteenth century.

In the seventeenth century, there was the Spanish domination which for a long time was accused by historiography of being the cause of the subsequent southern poverty. Personally, however, I believe that the moment of real crisis came precisely with the unification of Italy and therefore this question could not be affirmed precisely by a Piedmontese like Levi who, in exile, fell in love with Basilicata and told his tormenting charm. His visit to Matera highlighted the contrasts between scenic beauty and social poverty. The Sassi of Matera are today decanted as one of the greatest worldwide examples of Bio-architecture as for centuries it has been built with full respect for the environment. Matera rises on a side of canyons whose side walls have been carved out of the tuff mass by the corrosive action of the Gravina stream. Here, men have made homes by digging directly into the tuff material of the canyon, creating caves. These dwellings were built according to the orientation of the cardinal points and taking advantage of the difference in radiation between summer and winter, moreover inventing an ingenious rainwater collection system (which is why Matera is part of the UNESCO heritage). For millennia, the population has lived in this perfectly integrated system except from the beginning of the twentieth century when a housing surplus forced the inhabitants of Matera to occupy churches and stables to respond to a cogent housing problem. This is the Matera described by Carlo Levi, whose tales reached Parliament and decided to start depopulating the Sassi. The Italian State confiscated all the houses putting them in the state heritage and built the first modern city thanks to the contribution of the greatest Italian and foreign architects and engineers.

Levi’s infamous book was published in 1945, nearly a decade after his departure. Although he promised his friends in Aliano that he would one day return, it is said that he never did make it back there during his life. He did, however, in death. The Aliano cemetery that we see him visit in the film is his eternal resting place, and his paintings are on display at the Museo di Palazzo Lanfranchi in nearby Matera. In the film, his sister described the Sassi (Stone City) of Matera as a “crater full of caves” with “20,000 men and animals crammed together” and “a city destroyed by the plague.” That stone city today is the 2019 European Capital of Culture and the region of Basilicata was #3 on the New York Times list of 52 places to visit in 2018.

Veteran documentary filmmaker Luigi Di Gianni, who shot his films upon the very ground that Levi once walked, told me in a 2016 interview, “That world of peasants was marvelous. It was a world of extreme poverty but with values and with an unparalleled beauty and wonder that is no longer found.” This is the essence of Rosi’s film- an accurate and moving interpretation of Levi’s book, which expresses his love, admiration and respect for a people that endured centuries of hardships.

“Christ stopped at Eboli” will be playing at the Film Forum in New York through April 18. Click here (https://filmforum.org/film/christ-stopped-at-eboli) for more information and to watch the trailer.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian